Pool Heater Options: Gas vs Electric vs Heat Pump Comparisons

Quick Answer: Which Pool Heater Is Best for You?

If you’re short on time, here’s the bottom line: heat pump pool heaters are typically the best choice for homeowners who swim regularly in mild to warm climates, offering the lowest operating costs and solid environmental performance. Gas pool heaters excel when you need quick heating on demand or live in a cooler climate where air temperatures frequently drop below 50°F. Electric resistance heaters have become a niche option, best suited for very small pools or hot tubs in areas with unusually cheap electricity—their running costs are simply too high for most residential swimming pools.

| Feature | Gas Heater | Electric Resistance Heater | Heat Pump |

|---|---|---|---|

| Upfront Cost (2024 ranges) | $1,800–$3,500 installed | $1,500–$4,000 installed | $3,000–$6,000 installed |

| Monthly Cost (12,000–20,000 gal pool) | $150–$400+ | $300–$600+ | $50–$150 |

| Best Climate | Any (works in cold) | Any | Mild to warm (50°F+ air) |

| Heating Speed | Fast (8–12 hours for 10°F rise) | Moderate | Slow (24–48 hours for 10°F rise) |

| Environmental Impact | Higher (fossil fuel combustion) | Grid-dependent | Lower (no on-site emissions) |

Quick recommendations by usage type:

Occasional weekend use: A gas heater delivers quick heating when you need it without running all week—ideal for sporadic swimmers.

Daily swimming April–October: A heat pump maintains consistent temperature at a fraction of gas costs, making it the cost effective choice for regular pool use.

Indoor pools: Heat pumps work exceptionally well since indoor ambient air stays warm year-round.

Vacation homes: Gas heaters make sense since you can heat water quickly upon arrival without maintaining temperature while away.

Overview of Modern Pool Heater Options

Most residential swimming pools in North America today rely on either gas heaters or electric heat pumps for pool heating, with electric resistance heaters and solar pool heaters filling smaller market segments. The choice between these systems comes down to how you’ll use your pool, where you live, and how you balance upfront investment against long term costs.

This article compares three main categories:

Gas heaters (natural gas and propane)

Electric resistance heaters

Air-source heat pump pool heaters

All three serve the same core function—raising pool water temperature to comfortable swimming levels—but they differ dramatically in:

How they generate or transfer heat (combustion vs. direct electric vs. refrigeration cycle)

Operating costs based on local electricity and gas prices

Climate suitability and heating speed

Environmental footprint and long term savings potential

All cost and performance examples in this guide assume typical backyard in-ground pools between 10,000 and 25,000 gallons under 2024 U.S. conditions. Your specific results will vary based on pool size, local energy rates, and climate.

While this article doesn’t focus on solar thermal systems, solar heaters remain an excellent zero-operating-cost option for homeowners with suitable roof or yard space who can capture the sun’s energy effectively.

Gas Pool Heaters (Natural Gas & Propane)

Gas pool heaters have been the traditional choice for decades, and for good reason: they deliver fast heating regardless of outdoor air conditions, making them reliable workhorses in virtually any climate. Whether you’re dealing with cool night temperatures in early spring or need to quickly warm a spa for evening use, gas gets the job done.

Modern gas heaters commonly range from 75,000 to 400,000 BTU/hour and run on either piped natural gas or delivered propane (LPG). Typical applications include weekend-only pools, spas and hot tubs requiring 100°F+ water, and pools in cold climates where heat pump’s efficiency drops significantly.

Most new units achieve efficiencies around 82%–95%, with high-efficiency condensing models like the Pentair ETi 400 reaching 96% thermal efficiency—meaning nearly all fuel energy converts directly to pool heat.

How a Gas Pool Heater Works

The process is straightforward:

Your pool pump moves water through the heater unit

A burner combusts natural gas or propane

Hot combustion gases pass through a heat exchanger (typically copper, cupro-nickel, or titanium)

Water absorbs this heat as it flows past the exchanger

Warmed water returns to the pool

Modern units include electronic ignition and digital thermostats rather than standing pilot lights, improving both safety and energy efficiency. Unlike older models from the 1990s, today’s gas heaters fire only when needed and shut down automatically once target temperature is reached.

Realistic heating example: A 250,000–300,000 BTU gas heater can raise a 15,000-gallon pool from 75°F to 85°F in roughly 8–12 hours under mild conditions—heating your pool faster than any other option.

Because gas heaters generate their own heat through combustion, they don’t rely on ambient air temperature. This makes them suitable for fall, winter, and early spring operation when outside air drops well below comfortable levels.

Installation considerations:

Natural gas requires a properly sized gas line (often 1” or larger for high-BTU units) and typically permitting

Propane systems need a storage tank and periodic fuel deliveries

Proper venting clearances and combustion air requirements must be met

Advantages of Gas Pool Heaters

Very rapid temperature rise: Heat your pool from cold to swimmable in hours, not days—perfect for quick heating before guests arrive

Reliable performance in cold ambient air: Works effectively even when temperatures drop below 50°F, unlike gas heaters’ electric counterparts

Ideal for spas and hot tubs: Quickly reaches and maintains 100°F+ water temperatures

Best for intermittent use: No need to maintain temperature every day—just fire it up when you want to swim

Straightforward installation with existing gas service: If your equipment pad already has a gas line, adding a pool heater is relatively simple

Modern high-efficiency models reduce fuel consumption: 90%+ efficiency units lower operating costs compared to older equipment

Real-world scenario: A family in Chicago uses a 400,000 BTU natural gas heater for their short May–September swimming season. They heat the pool on Friday afternoons for weekend use, spending roughly $60–80 per weekend rather than maintaining temperature all week.

Disadvantages of Gas Pool Heaters

Running costs can be substantial. With 2024 fuel prices averaging $1.20–$1.80 per therm for natural gas and $2.50–$4.00 per gallon for propane, monthly bills can easily reach $200–$500 for frequent use. Propane runs approximately 70% less efficiently per dollar spent compared to natural gas.

Environmental impact is notable. Burning fossil fuel produces CO₂ and contributes to greenhouse gases. While outdoor residential units vent combustion gases safely, they still carry a larger carbon footprint than electric alternatives on clean grids.

Maintenance and lifespan considerations:

Burners and heat exchangers can corrode, especially with poorly balanced pool water or saltwater systems

Annual servicing is recommended to maximize lifespan (often 7–12 years)

High-chlorine or low-pH conditions accelerate wear on internal components

Installation can add costs. Permits, gas line upgrades, and combustion air/clearance requirements can add $500–$2,000+ to project costs depending on site conditions.

Propane logistics: Systems running on propane depend on timely deliveries and can be impacted by regional fuel shortages or price spikes during winter months.

Electric Resistance Pool Heaters

Electric resistance pool heaters warm water by passing electric current through heating elements—essentially an oversized version of an electric water heater or kettle. It’s important to understand that these are fundamentally different from electric pool heater systems that use heat pump technology.

Unlike heat pumps that move heat from one place to another, electric resistance heaters create heat directly. This distinction matters enormously for operating costs.

Pure electric resistance pool heaters are now uncommon for large in-ground pools due to very high operating costs. However, they still appear in:

Small above-ground pools

Hot tubs and therapy spas

Regions with extremely low electricity rates (parts of the Pacific Northwest, for example)

Indoor installations where venting combustion gases isn’t possible

Typical power draws range from 11 kW to 27 kW, requiring substantial electrical capacity and dedicated high-amperage breakers (often 50–125 amps).

How an Electric Resistance Pool Heater Works

The operation is simple: pool water is pumped across electric heating elements housed in a sealed chamber. As electricity flows through the elements, they heat up directly, warming the water passing by before it returns to the pool.

In energy terms, efficiency is effectively 100% at the point of use—all electricity becomes heat. However, electricity itself is expensive compared to the heat delivered by a heat pump operating at COP 5.0 or higher.

Cost example: A 20 kW electric heater running for 5 hours uses 100 kWh. At $0.18 per kWh (a common 2024 U.S. residential rate), that’s about $18 for a single heating session. Running this daily quickly becomes expensive.

These systems connect to standard pool pumps and filtration, requiring no gas line or combustion venting. However, they’re generally practical only for smaller water volumes (3,000–8,000 gallons) if the owner wants costs to remain manageable.

Advantages of Electric Resistance Heaters

Simplicity: Few moving parts, no combustion, no gas line, relatively compact units that can be wall- or pad-mounted

Straightforward installation: Where sufficient electrical service already exists (200-amp or larger panels), adding an electric heater can be simpler than running gas lines

Predictable, steady heating output: Works in any ambient temperature since they don’t rely on outdoor air warmth

Viable for specialty applications: Small therapy pools, indoor plunge pools, or regions with abundant low-cost renewable electricity

Note: For typical family-sized outdoor pools, electric resistance heating is generally not the recommended choice due to ongoing energy costs.

Disadvantages of Electric Resistance Heaters

Operating costs are typically the highest of all options. Running a 20–30 kW heater daily can easily exceed $300–$600 per month on typical 2024 U.S. electricity rates—far exceeding what you’d pay with a heat pump or even gas.

Electrical infrastructure requirements are substantial. Larger units may need 60–125 amp dedicated circuits, which can mean panel upgrades and higher electrician labor costs—sometimes adding $1,000–$3,000 to the project.

Heating large pools takes significant time and power. Raising a 15,000-gallon pool from 70°F to 84°F can consume massive amounts of electricity, making these impractical for most homeowners with standard-sized swimming pools.

Environmental footprint depends on grid sources. While there’s no on-site combustion, the overall impact depends heavily on how local electricity is generated—coal, natural gas, nuclear, or renewables.

Most pool professionals will steer customers toward a heat pump rather than electric resistance when an “electric” heating solution is desired.

Electric Heat Pump Pool Heaters

Heat pumps represent the primary modern “electric” pool heating option, using refrigeration technology to move heat from the surrounding air into pool water. They use the same principles as home air conditioners and residential HVAC heat pumps, but in reverse: they harvest warmth from outside air and transfer heat into the pool.

2024 efficiency context: Quality pool heat pump models achieve Coefficient of Performance (COP) values in the 4.0–7.0 range. This means 1 kWh of electricity can deliver 4–7 kWh worth of heat to the pool—a dramatic improvement over electric resistance heating.

Typical residential heat pump pool heaters range from 75,000 to 140,000 BTU output, with inverter/variable-speed models offering quieter and more efficient operation. Brands like Hayward HeatPro, Pentair UltraTemp, and newer models with inverter technology consistently achieve COP values of 5.0–6.5 in mild conditions above 50°F.

How a Heat Pump Pool Heater Works

The refrigeration cycle works as follows:

A fan pulls ambient air over an evaporator coil

Refrigerant inside the coil absorbs low-grade heat from the air and becomes a gas

A compressor raises the refrigerant’s temperature and pressure

The hot refrigerant passes through a condenser, releasing heat into circulating pool water

Cooled refrigerant cycles back to the evaporator to repeat the process

This process works most efficiently when outdoor air temperature is between about 60°F and 95°F. Most manufacturers specify a minimum effective operating temperature around 45–50°F, below which output drops significantly.

Efficiency example: At 80°F outdoor temperature, a 120,000 BTU heat pump with COP 5 delivers roughly 120,000 BTU of heat while consuming only about 24,000 BTU-equivalent of electricity (around 7 kW). That’s the energy leverage that makes heat pumps so cost effective for consistent heating.

Unlike gas heaters designed for quick heating, heat pumps are intended to maintain a desired consistent temperature over time rather than rapidly boosting a very cold pool in one day.

Advantages of Heat Pump Pool Heaters

Much lower operating costs: In suitable climates, heat pumps cut monthly pool-heating bills by 50–75% compared with gas for similar usage—often running $2–4/day versus $5–10/day for gas in South Florida scenarios

Environmental benefits: No on-site combustion, lower carbon emissions per unit of heat (especially on grids with significant solar, wind, or hydro power), and no risk of carbon monoxide

Perfect for extended seasons: Daily swimming from late spring through early fall with the unit efficiently maintaining 82–86°F water temperatures

Modern features: Many 2022–2024 models include inverter compressors for quieter operation and better part-load efficiency

Long lifespan: Quality units with titanium heat exchangers can last 10–15+ years with proper maintenance

Real-world example: A Florida homeowner keeps their 20,000-gallon pool at 84°F from March through November using a 120,000 BTU heat pump. Monthly electricity costs for pool heating average $80–120, compared to estimated $250–400 with gas—delivering significant energy savings over the swimming season.

Disadvantages of Heat Pump Pool Heaters

Climate limitations are real. As outdoor air temperature drops below roughly 50°F, output and COP fall sharply. At 45°F, output may drop by half, making heat pumps slower and less economical in cold shoulder seasons.

Heating speed is slower than gas. Raising a cool pool by 10–15°F may take 1–2 days of continuous running, so heat pumps are less ideal for occasional, on-demand usage at vacation homes or weekend-only pools.

Higher upfront cost: Units typically cost more than standard gas heaters, and installation may require a 30–60 amp dedicated 240V circuit and professional electrical work, increasing project budgets to $3,000–$6,500+ installed.

Noise considerations: While many units are relatively quiet (modern inverter models especially), they’re not silent. The fan and compressor produce audible sound and should be sited away from bedroom windows or property lines where possible.

Performance varies with conditions: Humidity, wind exposure, and use of a pool cover all affect efficiency. Without a cover, much of the gained heat can be lost overnight during cool night temperatures, lengthening run times and increasing costs.

Cost Comparison: Gas vs Electric Resistance vs Heat Pump (2024)

Understanding both upfront and ongoing costs is essential for making an informed decision. The figures below represent approximate 2024 North American residential averages—your local market may vary based on labor costs, permitting requirements, and equipment availability.

| Cost Category | Gas Heater | Electric Resistance | Heat Pump |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Equipment Cost | $1,500–$3,000 | $1,000–$2,500 | $2,500–$5,000 |

| Typical Installed Cost | $2,000–$4,500 | $1,500–$4,000 | $3,000–$6,500 |

| Monthly Operating Cost* | $150–$400 | $300–$600 | $50–$150 |

*Estimates assume a 15,000-gallon outdoor pool heated to 84°F in a mild climate with 6–8 hours/day run time during a typical month, gas at $1.50/therm, electricity at $0.16/kWh.

Key cost insights:

Heat pumps have the lowest annual cost for extended use in warmer climates despite the higher upfront cost

Gas heaters offer a lower initial cost but higher operational costs that add up quickly with regular use

Electric resistance has the lowest equipment cost but highest operating expenses—rarely cost effective for pools over 5,000 gallons

The break-even point between gas and heat pump typically occurs within 2–4 years for daily swimmers

Local utility rates can dramatically shift these calculations. In areas where natural gas is unusually cheap or electricity expensive, gas may remain competitive. Conversely, regions with low electricity rates and expensive propane heavily favor heat pumps.

Performance, Climate & Usage: Which Heater Fits Which Scenario?

The “best” heater depends on three main factors: climate (average temperature and season length), usage pattern (daily vs. weekend), and local energy prices. There’s no universal answer—only the right answer for your situation.

Scenario-Based Recommendations

Warm coastal climate with long swim season (Florida, Gulf Coast, Southern California):

Best choice: Heat pump

Why: Ambient air temperature stays above 50°F for most of the year, allowing heat pumps to operate at peak efficiency. The long swimming season (8–10 months) maximizes energy savings compared to gas.

Cool or four-season climate (Midwest, Northeast):

Best choice: Gas heater or dual system

Why: Cooler climates with ambient air regularly below 50°F limit heat pump effectiveness. Gas heaters work in any weather and provide quick heating for the shorter swim season.

Mountain or high-elevation region:

Best choice: Gas heater

Why: Cooler nighttime temperatures, shorter seasons, and often intermittent use make gas’s quick heating capability more valuable than heat pump efficiency.

Indoor or screened-in pools:

Best choice: Heat pump

Why: Controlled environment means consistent warm air supply. Heat pumps thrive in these conditions with excellent year round heating potential.

Spa/hot tub alongside pool:

Recommendation: Gas for the spa, heat pump for the main pool

Why: Spas need to reach 100°F+ quickly for short-duration use. Gas delivers this speed; heat pumps are better for maintaining a large pool’s steady temperature.

Decision Checklist

Ask yourself these questions:

How many months per year will I swim year round or at least regularly?

What are local electricity and gas prices per kWh and therm?

Do I need quick heating for occasional use, or consistent heating for daily swimming?

Does outside temperature in my area drop below 50°F during my desired swim months?

Am I prioritizing lower upfront cost or long term savings?

How important is being eco friendly in my purchasing decision?

Sizing, Installation & Efficiency Tips

Proper sizing and professional installation are essential for any heater type to achieve expected performance and cost efficiency. An undersized heater struggles to maintain temperature; an oversized unit short-cycles and wastes energy.

Sizing Basics

Heat output (BTU/hour) must match:

Pool’s surface area and volume

Desired temperature rise above average temperature

Wind exposure in the pool area

Whether a cover will be used at night

General BTU guidelines:

| Pool Size | Recommended BTU Range |

|---|---|

| 8,000–10,000 gallons | 50,000–75,000 BTU |

| 12,000–20,000 gallons | 100,000–140,000 BTU |

| 20,000–30,000 gallons | 140,000–200,000 BTU |

| Larger or exposed pools | 200,000–400,000 BTU |

For heat pumps, the calculation also considers minimum ambient air temperature during your swimming season. In warmer climates, a smaller unit can maintain temperature efficiently; in cooler climates, oversizing slightly helps compensate for efficiency losses.

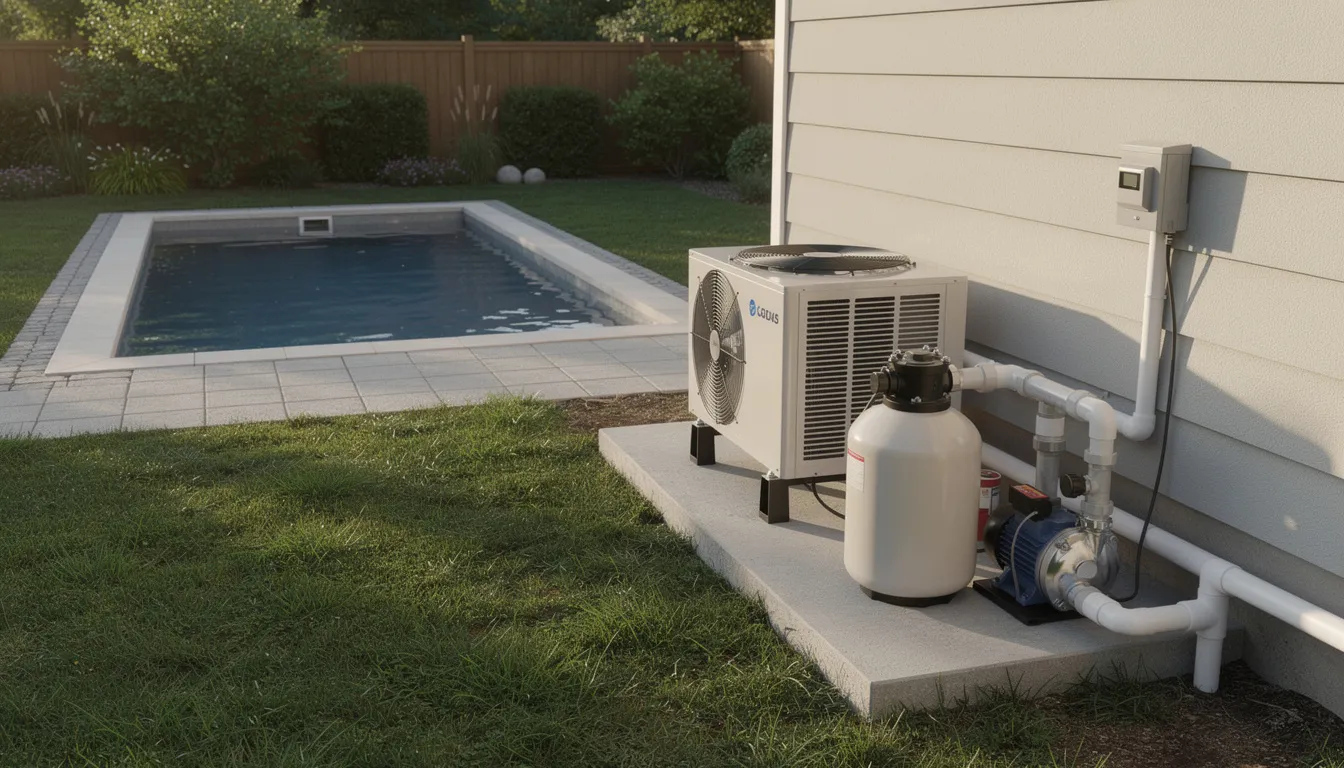

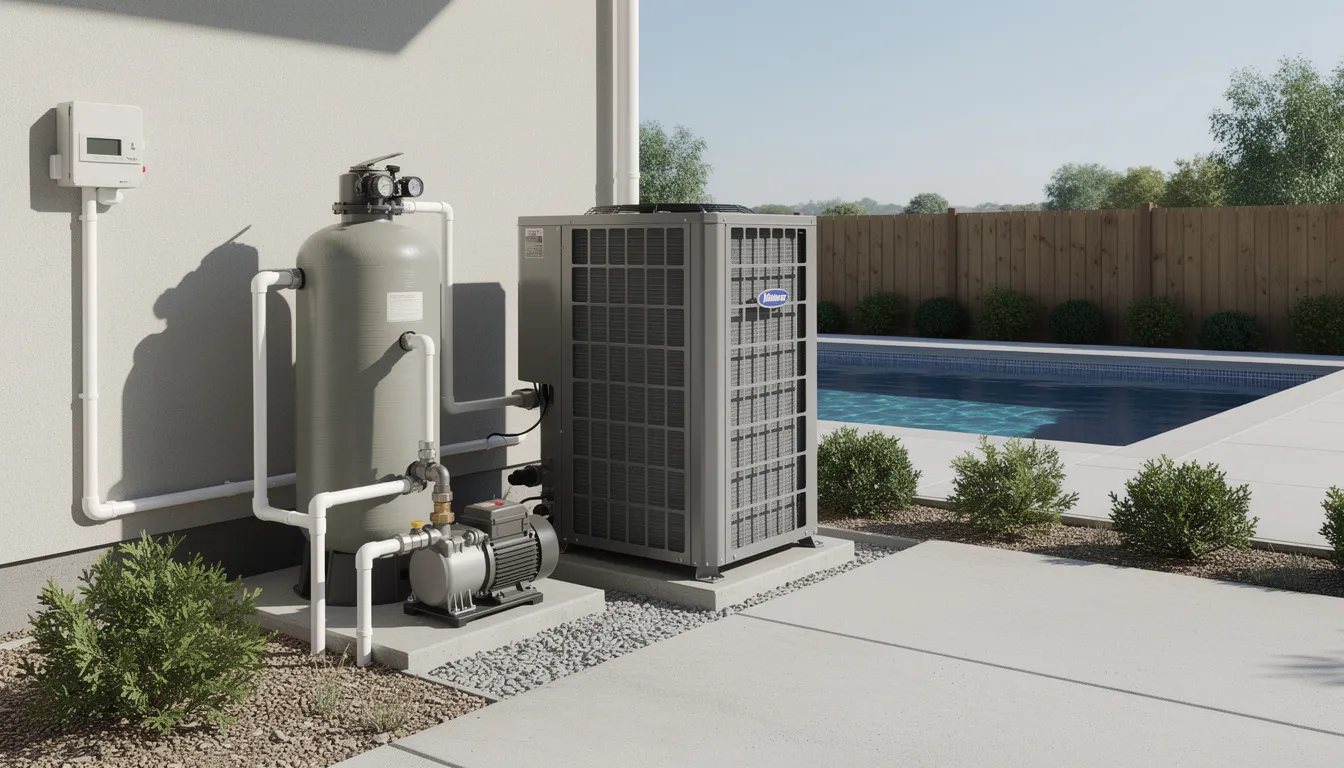

Installation Considerations

For gas heaters:

Gas line must be sized to the heater’s BTU rating (consult a licensed plumber)

Venting clearances from structures and property lines per local codes

Adequate combustion air supply

Permits typically required

For heat pumps:

Dedicated 30–60 amp 240V circuit

Adequate breaker panel capacity

Equipment pad space with airflow clearance (typically 24”+ on all sides)

Placement away from windows and neighbors for noise reduction

Coordination with pool pump operation

Efficiency Tips for All Pool Owners

Always use a pool cover at night: Solar covers and thermal blankets can reduce heat loss by 50–70%, dramatically reducing run times and costs

Lower setpoint when not in use: Dropping temperature 3–5°F when the pool sits idle for several days saves significant energy

Keep filters clean: Proper water flow through your pool pump and heater maintains efficiency and prevents strain on equipment

Schedule regular professional service: Annual maintenance (or as per manufacturer guidance) extends equipment life and catches problems early

Consider a variable-speed pool pump: Modern variable-speed pumps reduce electricity use by 50–80% compared to single-speed models and pair excellently with heat pumps

Frequently Asked Questions About Pool Heating Options

How long do pool heaters last?

Gas heaters typically last 7–12 years depending on water chemistry, usage frequency, and maintenance costs investments. Heat pumps often reach 10–15+ years when properly maintained, thanks to titanium heat exchangers that resist corrosion. Electric resistance units fall in a similar range but can deteriorate faster if water chemistry is poor. Proper maintenance extends lifespan significantly for all types.

Can I use a heat pump in a cold climate?

You can, but with limitations. Heat pumps work effectively when outside temperature stays above 50°F. Below that threshold, efficiency drops sharply and heating slows considerably. In cold climates, many homeowners use a heat pump for the core season (June–August) and either close the pool during cooler months or add a gas heater as backup for extended seasons.

Is it cheaper to keep my pool at a steady temperature or heat it only when needed?

For heat pumps, maintaining a consistent temperature is usually more economical—the system runs efficiently at part-load to compensate for overnight losses rather than working hard to recover lost degrees. For gas heaters used occasionally, heating only when needed often makes more sense, since you avoid paying to maintain temperature during days when the pool sits unused.

Can I combine a heat pump with solar panels or solar thermal?

Yes. Rooftop solar panels can offset the electricity a heat pump consumes, effectively creating a near-zero-operating-cost system. Solar thermal collectors (separate from photovoltaic panels) can also pre-heat pool water, reducing the load on any heating system. This combination offers excellent cost efficiency and minimal environmental impact for pools in sunny regions.

Which option is most eco friendly?

Heat pumps generally offer the lowest environmental impact, especially when powered by clean grid electricity or paired with home solar panels. They produce no on-site emissions and use less energy per unit of heat delivered. Gas heaters, while effective, burn fossil fuels and produce greenhouse gases. Electric resistance heaters’ impact depends entirely on how local electricity is generated—on a coal-heavy grid, they can have a surprisingly large carbon footprint.

Does pool size significantly affect heater choice?

Absolutely. A large pool (over 25,000 gallons) requires more BTUs to heat and maintain, which amplifies operating cost differences between heater types. For large pools in warm climates, heat pumps offer substantial long term savings. For very small pools or hot tubs, the cost differential narrows, making convenience and speed more relevant factors.

Key Takeaways

Heat pumps deliver the lowest operating costs for regular swimmers in mild to warm climates, typically cutting costs 50–75% versus gas

Gas heaters remain the best choice for quick heating, cold climates, spas, and intermittent use

Electric resistance heaters are now a niche option—avoid them for standard swimming pools unless electricity is exceptionally cheap

Proper sizing, professional installation, and consistent pool cover use maximize efficiency for any system

Your ideal pool heater size, climate, and usage pattern together—not just one factor

Before making your final decision, get quotes from local pool professionals for both gas and heat pump installations. Compare the installed costs against projected operating expenses based on your local utility rates, and factor in how often you’ll actually swim. The right heater pays for itself in comfort, reliability, and manageable long term costs.